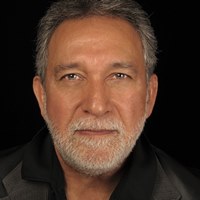

New! To read an interview with Gervasio, please Click Here.

New! To read an interview with Gervasio, please Click Here.

Gervasio Arrancado was born in a small shack in Mexico and raised in the orphanage at Agua Idelfonso, several kilometers, give or take a few, from the fictional fishing village of Agua Rocosa. He is fortunate to have made the acquaintance of Augustus McCrae, Hub and Garth McCann, El Mariachi, Forest Gump, The Bride (Black Mamba), Agents J and K, a very old man with enormous wings, Juan-Carlos Salazár, Maldito, the chupacabra and several other notables. Gervasio visits regularly with his friend Nick Porter, whom he fondly calls Paco (nobody knows why, but we’re all certain he has his reasons), and with Juan-Carlos Salazár, whom he calls his colaborador in all things literary. To this day he lives and writes at that place on the horizon where reality folds into imagination. Below is one of his many stories. Enjoy.

* * *

The Dawn of Rigoberto

The men had just struggled ashore from their boats and were looking forward to joining their women and children in their homes, from which soft lights were beginning to emanate as the sun gave up the day. As a few were busily stowing what must be stowed, most were emptying the hold of the day’s catch, creating a new reality for the fish they’d caught, who were becoming the vendors’ concern. As the fish made the transition from captives to wares, the vendors variously cleaned and iced and chopped and salted them in preparation for the next morning’s sales.

A very small wooden shack, grey with decades of weathering and salt spray, was situated just across the dock from the largest boat. As an occasional gust of wind blew in from the sea, the old door slapped the side of the shack, its hinges complaining loudly, then pushed itself a few inches away from the wall as if spurning an unwanted lover. Then it hesitated as if fickle before slapping the side of the shack with less anger.

It was not only the end of another long day, but the end of the month. Inside the shack, Rigoberto, the captain of the largest boat, was doling out his crewmembers’ wages plus a modest bonus for the excellent catch. He was the largest man in town, easily standing a head taller than all others, and the handsomest, with a look that was born of the sea and his father, whom, to his knowledge, he had never met: Rigoberto was weathered but not worn, ageless but not aged. His physical prowess and temper were unmatched. Everyone took note of the former, of course—the women as in a dream state and the men with a great deal of envy—but fortunately very few had encountered the latter, as the kindness and respect with which he treated those within his charge also was unmatched. When the last of his crewmembers had left for home, Rigoberto stepped around the table and through the door, then closed the door securely and latched it with a small piece of wood that turned on a nail. He glanced over his boat a final time, giving his livelihood its due, then turned for home.

As Rigoberto strode up the wide dirt street, he glanced up at La Montaña de Sueños Cautivos, The Mountain of Captive Dreams. The mountain captured not only the dreams of the villagers, nesting and nurturing them and then allowing them to seep back down to the village when they were sorely needed, but also the imagination of any who believed in legends, as most in the sleepy village did. Rigoberto believed more than most, and for a much stronger reason than the wealth of dreams stored there. Rigoberto’s mother had wandered off to the mountain within a few weeks of his birth.

His uncle, who had raised him, had been swept overboard and lost the previous year, and his aunt had died along with her new son in childbirth some twenty years earlier, so his mother, if she were alive on the mountain, was his only living relative. The mountain was his touchstone.

The villagers had sensed that the woman who had given birth to Rigoberto was different, especially as they witnessed the speed with which he grew physically and intellectually. Many had thought—secretly, of course, for it wasn’t prudent to be less than secretive about such things—that she was a witch and perhaps even a consort to the sea itself. Indeed, when a generation had come and gone since she’d wandered away, she had grown in the minds of many from witch to goddess. The villagers shook their fists and issued stern warnings (while keeping one wary eye on the mountain, of course) when inclement weather lasted longer than they considered natural or when lightning strikes came closer than was comfortable, and they offered up loud prayers of allegedly never-ending gratitude when the fleet returned with their holds full of fish or when the rains came when they were welcome or stopped when they were not. Thus had Rigoberto’s mother garnered a great deal more responsibility than she ever would have wanted.

As he glanced up at La Montaña de Sueños Cautivos, in a clearing near the peak he detected the hint of a creature, descending slowly. He continued along the dusty street, but averted his gaze and frowned. The mountain has always been densely covered with jungle; there are no clearings. When he was twelve he’d been to the top once with his uncle, “To see the home of the ancient and future king,” his uncle had said, but he was certain the man had hoped to find his sister, Rigoberto’s mother. The trek had taken them the better part of a day, following a stream that the father of the future king himself inadvertently had followed when he thought to separate himself from the world. That he wasn’t successful in secluding himself was a good thing, Rigoberto thought. Everyone in the village had heard the story. Had the man not eventually been overcome with loneliness and come down from the mountain, he would never have met the mother of the future king, and the king himself would still be waiting in the ether for an appropriate set of parents. Rigoberto had expected a castle, or at the very least a large dwelling (and in a back corner of his mind, he secretly hoped they would find his mother), but when he and his uncle had arrived at the top, the king’s home was little more than a cave with a pool nearby. And of course, his mother was nowhere to be seen.

Rigoberto had looked up at his uncle, disappointment evident in his face. “But there is no throne, Tio. How can a king rule with no throne?”

“Ah but there is, my son,” his uncle had said. “The throne is a holy circle, and it’s on the roof. Only the king can see it, and only the king, when he’s seated in its exact center, is given a view all the way to that horizon where imagination folds into reality. He knows and commands earth, wind, fire and sea. Thus is his wisdom multiplied and his subjects prosper in peace.”

“And no others could employ the same vision?” Rigoberto asked, for he already had heard the whispered rumors in town concerning his mother.

“No, she couldn’t—I mean, no… only the king would be given such vision.”

As he walked, Rigoberto glanced at the mountain again. It was a solid green canopy. The clearing he thought he’d seen only seconds earlier and its occupant were gone, a figment of his imagination dusted away on the light breeze coming in from the sea. Then, just as he started to avert his gaze again, There! Just over halfway down the mountain, the same creature he’d seen near the top had appeared again. No doubt in another clearing that doesn’t exist, he thought, then smiled and shook his head. It has been a very long day. But before he looked away this time, he glanced quickly again and saw that the creature was actually a crone, bent at the shoulders and perhaps leaning on a walking stick as she made her way down the mountain.

His heart seemed to double its pace as he considered the possibilities. Then his thoughts shifted from the crone to the speed with which she was descending. Very swiftly, he thought, a bit surprised. If she were the same creature he’d seen in the disappearing clearing near the top, she had descended well over a thousand feet in less than a minute, and that caused his thoughts to shift yet again, from his mother to the goddess of the rumors, just as if he were certain in his soul—or perhaps merely hopeful—that they were two different beings. He glanced up again to confirm his suspicion, but the clearing was gone. He sighed as his anxiety waned. A long day, but a good day. He turned left at the corner and continued toward his home.

It was an auspicious day.

Rigoberto had opened a few cans of whatever he thought might combine well, poured them into a single stew pan and set them atop a very low fire to let the various flavors work out the details. He had settled into his favorite chair when a thought came to him from the outside in, as if he were eavesdropping. I’m telling you, it’s time.

Time for what? he thought, then said, “Time for what?” When he suddenly realized he was talking to himself he shook his head and grinned. Time for a vacation, perhaps.

The sea sent a breeze to rattle the seaward shutters as another thought occurred, slightly more intense, for a thought cannot be characterized as louder or quieter. He has reached his thirty-third anniversary. It is time.

As if he had no choice, Rigoberto thought, He? Who is he? A strange sensation of being on the precipice of knowledge trembled through him and he looked about the room. He murmured, “Am… am I ‘he’?” Of course, he was alone in the room and immediately felt foolish.

It is time. You must come to know your father.

The shutters rattled again, and Rigoberto stood, turning frantically this way and that. “Me? My father? Who are you? How do you know—”

Be calm, my son. All is well. Be calm and you will know. Be calm…. Be calm….

A sweet aroma wafted through the room, reminding Rigoberto of the stew. He went into the kitchen, welcoming the normalcy of the action as a catalyst to reattach himself to reality while regaining control of his senses. A moment later, as he removed the pan from the fire and set out two bowls and two spoons, an eerie calm settled over him. She’s right… all is well. We will share a meal… and I will meet my father.

The shutters on the seaward side of the house rattled again, lightly, as if with glee, but Rigoberto was moving toward the front of the room. Just as he got there a knock sounded. He opened the door and his arms. “Tierra… mi madre, Tierra….”

A small woman, bent at the shoulders, nodded. “Mi hijo… my son…..”

He smiled and gathered her into his arms, gently. “Mama, tu eres mi corazón. You are my heart.”

“Oh sí.” She smiled up at him, pinched his cheek, and leaned her walking stick against the wall near the door. They went to the small table, where they shared a meal of stew and dark bread.

*

An hour later, on their way to the shore, she said, “Having enticed the sea and become with child, I ascended to await the king to beg his forgiveness and receive guidance. I was allowed to watch over you, but as penance it was always from that place where horizons converge. Today you receive your birthright… today, again I become only memory.”

On a massive rock just northwest of the village, she smiled and hugged Rigoberto, then turned away and raised her hands over the sea. “Neptuno, behold your son, of earth and sea!”

As a great spiraling wave rose up, rapturous ripples wafted through Rigoberto, each filling him with more strength, power and wisdom. The spiral engulfed the rock upon which he and his mother were standing, and they began to spin. Rising, they spun more and more tightly until Tierra blinked out of existence and everything flashed to a stop.

Rigoberto awoke on his back on the beach. He looked about. Nobody else was there, but he sensed he was not alone. He sifted a bit of earth through his fingers. Then he rose, stretched one hand toward the sea and watched as the whitecaps became smooth. He smiled, turned and walked back to the village, his sea-green eyes reflecting creation itself.

* * * * *